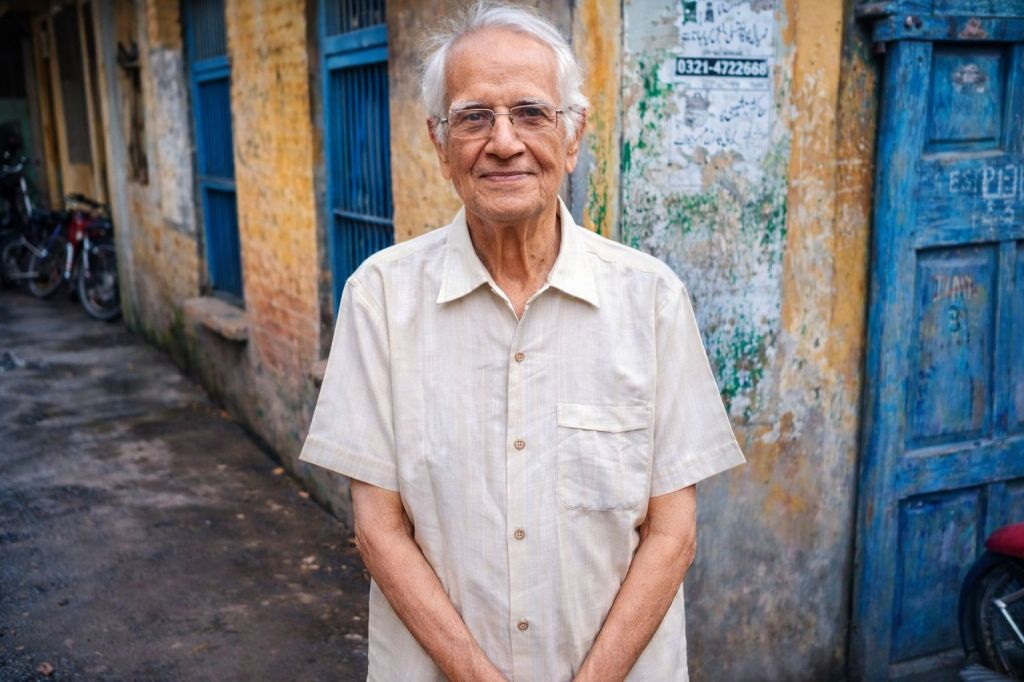

Zein Ahmed’s relationship with fashion has never been about novelty. It has always been about memory. Long before sustainability became an industry mandate, her understanding of clothing was shaped by a quieter, more enduring logic—one learned at home, in Lahore, where objects were valued for how they were made, not how quickly they could be replaced.

“I grew up surrounded by women, by handwoven textiles, by things that lasted,” she says. The youngest of five sisters, Zein was raised in a household where organic food was the norm, not a trend, and where what you wore mattered as much as what you consumed. “My parents had a deep appreciation for the old world. Handwoven fabrics, vegetable dyes, traditional classics—those always mattered more than trends.”

That early grounding would later become the backbone of two businesses built decades apart, on different continents, yet bound by the same belief: that craft is not ornamental, and labour is never invisible.

When Fashion Moved Fast, She Took Her Time

When Zein moved to New York in 1998, the global fashion industry was accelerating. Fast fashion was gaining ground, production was becoming increasingly detached from people and place, and sustainability—if it appeared at all—was confined to the margins. The prevailing mood was excess.

Zein enrolled at the Fashion Institute of Technology to study fashion design, supporting herself through a patchwork of part-time jobs. Over time, her curiosity shifted toward another world entirely. She completed an Associate’s degree in restaurant management, a business-focused programme that sharpened her understanding of operations, margins, and systems. “The principles are the same for any business,” she says simply. “Whether it’s a restaurant or a fashion label.”

She trained at the Institute of Culinary Education and worked both front and back of house at some of New York’s most respected restaurants, including under acclaimed chefs Anita Lo (Annisa) and the late Floyd Cardoz (Tabla). Kitchens taught her discipline, stamina, and respect for process—but they were also physically punishing and creatively limiting.

“I did it out of sheer will for the first ten years,” she reflects. “The work was repetitive, exhausting, and often invisible. Kitchens are windowless. Menus don’t change for years. You carry loads heavier than yourself and do the same motions every day.” By her early thirties, the toll was undeniable. “At some point, I realised I was bored. And I couldn’t imagine doing that forever.”

What stayed with her, however, was a clear-eyed understanding of labour—who does it, who benefits from it, and who is rarely seen.

Learning the Market from the Inside

Alongside restaurant work, Zein spent nearly two decades immersed in the luxury fashion trade-show circuit. She worked extensively at NY NOW, ENK, Coterie, Moda, and others—sometimes as a fit model, often as a part-time sales associate helping brands secure large-ticket wholesale orders.

“I was on the floor, writing orders with buyers, helping stores decide what would actually sell,” she says. “That’s where I learned what luxury stores look for, how buyers think, and why certain products move.”

This wasn’t theory—it was lived market education. She observed pricing psychology, merchandising decisions, and the fine line between aspiration and accessibility. “Everything I learned there, I later used to launch Guru.”

Building Something by Hand

Guru New York launched in May 2008, quietly and without spectacle. It arrived at a moment when the industry was ill-prepared for restraint, yet searching—perhaps unconsciously—for meaning. Guru produced apparel, footwear, and jewellery rooted in a clear, uncompromising ethos: slow fashion, ethical sourcing, and sweatshop-free manufacturing.

The early days were stitched together by community. “Friends and strangers came together to support me in ways I could never have imagined,” Zein says. Her 300-square-foot Chelsea apartment doubled as a studio, walls covered in printed designs and idea maps. A housemate designed the logo and website.

A friend modelled for photoshoots staged in her sister’s apartment using giant white poster boards as backdrops. Trunk shows were hosted in Brooklyn living rooms. Weekends were spent at SoHo markets, Green Flea, and Brooklyn Flea—where Zein was among the earliest vendors.

“At the time, I was still working full-time,” she says. “Perhaps 20 hours a day.”

Momentum followed. Holiday markets led to wholesale orders. Trade shows and charity events expanded Guru’s reach. Within three years, the brand was stocked in nearly 200 boutiques across the US and Europe, including Milan, Paris, and Switzerland. With a personal investment of just $3,000, Guru crossed $500,000 in sales.

Coverage followed—Oprah’s O Magazine, Vogue, Marie Claire, The New York Times, MSNBC, CBS Morning News. Still, Guru resisted scale for its own sake. “Less is more was always our ethos,” Zein says. Textiles were sourced from New York’s garment district. Manufacturing was split between New York and Lahore. Child labour was never tolerated. Cottage industries were actively supported.

Even celebrities took notice—Bette Midler, for instance, purchased multiple Guru tunics, drawn to the brand’s elegance and ethical ethos. Guru’s sandals, crafted by artisans in Pakistan, marked a pivotal moment. The brand’s first wholesale order came from Calypso St. Barth, the New York–based luxury resortwear label. They ordered for all 27 of their boutiques. The sandals sold out within two weeks.

Not long after, Guru was listed among Oprah’s favourite resortwear brands in O Magazine’s June 2016 issue, a quiet but powerful validation of the label’s philosophy.

“That moment affirmed everything,” Zein reflects. “It showed me that when integrity leads, the market follows.”

Love Handmade: A Return, With Intention

If Guru proved that ethical fashion could succeed globally, Love Handmade – founded in 2020 in Islamabad—is about ensuring that global markets work for the people behind the craft.

Love Handmade partners with 125 female home-based artisans across 10 villages in rural Sindh. The work extends far beyond production. Artisans receive training in design, quality control, financial literacy, digital skills, and entrepreneurship. They are connected to national and international buyers not as beneficiaries, but as professionals.

“There’s a tendency to romanticise craft, especially when it’s done by rural women,” Zein says. “But admiration without fair pay is exploitation.”

Love Handmade rejects charity narratives entirely. Its mission is grounded in dignity—paying market-based wages, preserving techniques like ralli, ajrak, quilting, and basketry through demand rather than donation, and integrating women into global markets despite mobility, cultural, and digital barriers.

Zein’s ability to bridge worlds is rare. She understands luxury fashion and global trade as fluently as she understands village-based production. Her recent consultancy with the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), designing programmes for financial inclusion and digital literacy for rural women, reflects that dual fluency. Since its inception, Love Handmade has been featured in Forbes, DAWN, Khaleej Times, and The News, among others. Its US pop-ups and trunk shows in 2025 sold out entirely—quiet proof that ethical work, when executed with excellence, resonates far beyond borders.

What Endures

Zein Ahmed’s work resists spectacle. It doesn’t shout. It doesn’t rush. It insists that craft is skilled labour, that heritage is contemporary, and that women working from their homes are not peripheral to the economy, but central to it.

“When you are on the right path,” Zein says, “the universe conspires to make it happen for you.” It’s a belief earned through years of risk, repetition, and trust. With both Guru and Love Handmade, her products bear witness—to a lineage of artisans, to hands that have worked through economic pressure, invisibility, and erasure, yet continue to create with precision and pride. Each piece carries tangible evidence of survival and knowledge passed carefully from one generation to the next.

It is from this continuity that Zein’s work draws its core conviction, that what is made with care lasts longer, travels further, and leaves behind more than an object.

Leave a comment