By Sarosh Ibrahim

I opened my eyes in a home with many rooms, the kind that allowed a child to disappear for hours with her books. If it wasn’t books, it was music. Madam Noor Jehan’s melodic Punjabi songs filled my parents’ room, spilling into the corridors of a house in Peshawar that, at the time, felt like my whole world. That was my first unconscious relationship with language, long before I understood what it meant to belong to one.

At eight-years-old, I moved to Lahore. Our lives were packed into boxes and transported in a large moving truck, carrying my parents, my brother, and a child who did not yet know she would spend the next two decades explaining herself. What eight-year-old understands roots? Yet the questions came quickly and without mercy.

What’s your caste? Are you a Pathan? Do you speak Pushto?

When I answered differently, confusion followed.

What is Hindko? Are you from Abbottabad? Do people in Peshawar speak anything besides Pushto? Is Peshawar your village?

Lahore taught me early that identity in Pakistan is rarely singular. I stopped trying to befriend girls at school, convinced we would return home in a few years. That return never came. Instead, Lahore stayed, and I stayed with it, suspended between memory and adaptation.

My first exposure to this inner turmoil arrived years later at Kinnaird College, during a class discussion on Saadat Hasan Manto’s Toba Tek Singh. While nothing compares to the violence of Partition 1947, the story gave language to a quieter unrest I had lived with for years, the feeling of being tethered to multiple places and fully claimed by none. Our textbooks insisted we were Pakistani before anything else, yet lived experience taught me otherwise. Being Pashtun, Punjabi, Sindhi, or Baloch often mattered more.

I was a Pakistani woman living in the most populous city of Punjab, yet constantly reduced to the house address printed on the back of my identity card. Every NADRA visit felt like a small interrogation. A routine question, followed by a pause and a look, was enough to remind me I was an outsider. When my father finally bought a house after years of living in rented spaces, I insisted we update our address. It mattered to me more than I wanted to admit. It said Lahore now. Still, the feeling of incompleteness remained.

During my college years, my world slowly retreated from physical spaces and expanded online. Social media became a place of possibility. I was searching for women who looked like me, who lived away from home, who understood goodbye not as a moment but as a pattern. I had always wanted to help people, once believing medicine was the only respectable path to service. Instead, I discovered that building community could be just as impactful.

I began writing blog posts about living away from my hometown and constructing a life in a city that didn’t quite accept me. Eventually, I sat in front of a camera and started speaking honestly, without scripts or strategy.

In 2022, at the age of 24, I launched Dear Body, a digital space and podcast rooted in conversations around women, identity, visibility, and selfhood. A friend once told me I was brave for doing so. I didn’t realise then that survival, especially as a woman online, is often mislabeled as courage.

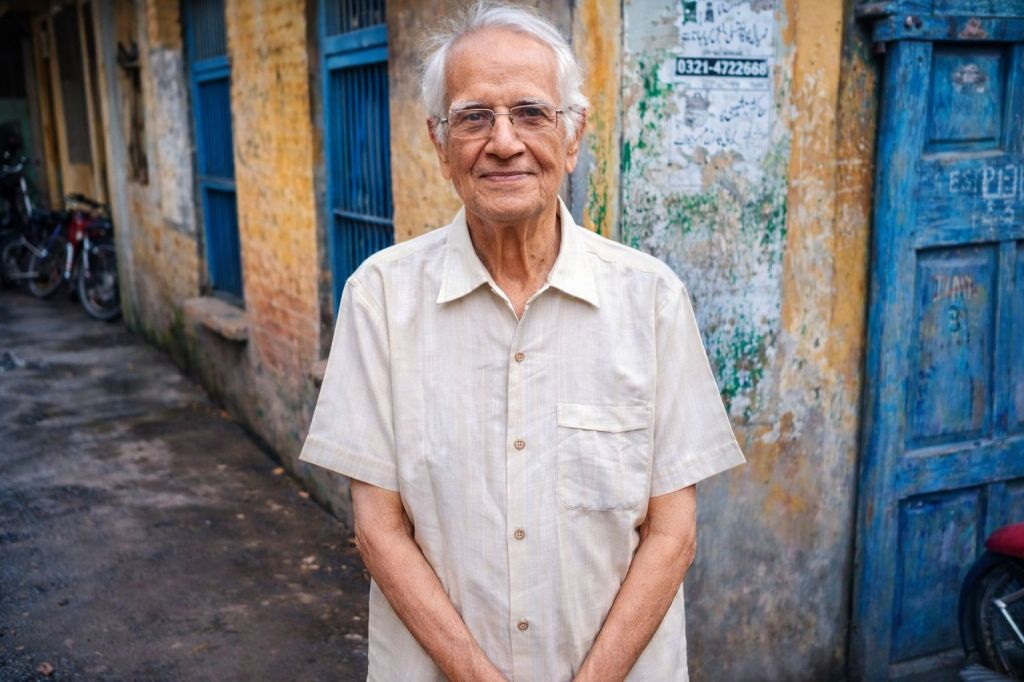

In 2024, I was approached by my uncle, who had reclaimed our ancestral home, the Mian Abdul Karim Sethi Haveli in Sethi Mohallah, Peshawar, with plans to turn it into a living museum. He asked me to help document its history digitally. Working closely with him awakened a pull I hadn’t felt in years. Peshawar greeted me with familiarity, with the scent of fresh Afghan naan and the cadence of voices that sounded like memory. Standing in that haveli, where my grandmother took her first steps, I felt something settle.

Months later, during the winter of 2025, I joined a Lahore Ka Ravi storytelling walk. Moving through the city with strangers, listening to histories layered into its streets, I realised how deeply Lahore had shaped me. The walk ended at Nau Nihal Singh Haveli, where stories of women’s suffering and erasure were too dense for me to walk in those rooms. I stood still as others moved through the Haveli, reimagining the countless lives our textbooks choose not to remember. It struck me then that while Lahore may not hold my ancestral home, it had given me something equally enduring: a voice.

Today, at 28, when people comment on my work and how I center women’s stories, I often think of the girl who once searched for a home in this city. When others joke about outsiders moving to big cities for education or opportunity, I smile. My roots may not certify my Lahori-ness, but this city speaks through me when I speak for women whose stories have been silenced.

Looking ahead, my work remains anchored in storytelling: through Dear Body, through digital archives, and through documenting women’s stories that have long been ignored or erased. Lahore continues to be the city that sharpened my voice and taught me that home is not always inherited. Sometimes, it is carved out of every wound that reminds me why I reclaimed Lahore as mine.

The author is a Lahore-based digital storyteller, podcast host, and communications professional. She is the founder and host of Dear Body, a Pakistani platform that examines body politics, identity, gender, freedom, and the everyday experiences of women navigating both public and private spaces. Her work focuses on storytelling, cultural memory, and reclaiming narratives that are often ignored or erased, particularly those of women.

Leave a comment